Practice as Research

Reflecting and Remixing:

Hip-Hop Retelling of the Life of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia

A Hip Hop Theatre piece included in the Punahou School Event -

“The Mo‘olelo of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia”

Jonathan Clarke Sypert

https://www.jonathanclarkesypert.com/portfolio-1/practice-as-research

Abstract

Henry ʻŌpūkahaʻia is historically known as one of the first Native Hawaiians to become a Christian, inspiring American Protestant missionaries in New England to come to Hawaiʻi during the 19th century. Punahou School was established by some of these missionaries and the approaching date of February 17th, 2018 held great significance as it marked the 200th anniversary of ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s passing. In the fall semester of 2017, Punahou School Chaplain Lauren Medeiros invited multidisciplinary artist Jonathan Clarke Sypert to join a collaborative team to create a Hamilton-inspired piece of musical theatre for middle school students grades six through eight, that would celebrate the life of a significant figure in Punahou’s origin story. Retired Punahou faculty Marion Lyman-Mersereau authored a five-page poem encapsulating key moments in ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s life journey, and Jonathan Clarke Sypert was contracted to compose music, write a libretto, choreograph, and direct a show derived from that poem. Punahou drama faculty, Heather Taylor served as Assistant Director and Costume Designer. The resulting production was titled A Hip Hop Retelling of the Life of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia. The epistemological journey to create this work included ethnography, theology, and dance offering theoretical paradigms to understand hip hop as a vehicle for knowledge transfer and the production of storytelling. Throughout the creative process, the cast of young artists and production crew were asked how personal experiences as lifelong learners may be effectively translated through live embodied performance. Grounded in vocal production and movement practice, the young artists also inquire how calling upon their ancestry and reflection on their place in their communities situates them as responsible artists in Hawaiʻi.

Keywords - Arts Education, Historical Musical Theatre, and Hip Hop

table of contents

Introduction - Origin Story

The Creation process

Missed Opportunities to Apply Methods

Conclusion: Thoughts for Future Production

Bibliography

“All new everything

I've got a feeling

This is my day to take a leap and I'm thinking

This little thing sleeping in my spirit

Don't have the words yet

It's so appealing to me”

- All New Everything, Scene Three

Introduction - Origin Story

Six years have passed since I became a partner in the celebratory events mentioned in this paper. This document serves to provide both a record of my contributions, as well as a point of reference for my reflections on the process. This paper became a practice in hermeneutic phenomenology and has enhanced my reflexivity in a way that inspires me to humbly reach out to my former collaborators, as well as to parties I did not include in this process. This paper is at once an expression of gratitude for the responsibilities entrusted to me, the invaluable gift of the experience of participating in this endeavor, and an acknowledgment of lacunae in the intentionality of my process during the stages of production. Going forward I will strive to fill these gaps in my practice with vigilant application of research methodologies including situating my research with Indigenous Research Methods by way of Shawn Wilson’s suggested Indigenous Research Paradigm, Dance Dramaturgy, Place-Based Learning, and Cultural Unlearning.

In September of 2017, I was approached by Chaplain Lauren Medeiros to see if we could take elements of the groundbreaking musical Hamilton and apply them to the life story of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, who is historically known as one of the first Native Hawaiians to become a Christian, inspiring American Protestant missionaries in New England to come to Hawaiʻi during the 19th century. To be honest, I was a bit daunted at the prospect of creating what I thought should be a feature-length musical, steeped in Hawaiian history with accuracy and facts, with a production value approaching Broadway. My first steps were hesitant, and days turned to weeks as we continued our talks.

Chaplain Medeiros and I had known each other for nearly a decade at this time and she knew me from my performance with her daughter in Hairspray at Diamond Head Theatre and my work as a spoken word artist, hip hop dancer, and performing arts educator. For her, I was a natural fit to helm this production. The real question was, is there enough time to create the music, lyrics, script, choreography, and costuming for this original musical by January? We decided to channel the bold and adventurous spirit of the real-life ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia who lept at the opportunity to board the Triumph. We decided to go for it.

After reading Lyman-Mersereau’s poetry, I understood how Chaplain Medeiros quickly envisioned how it might be turned into a piece of theatre that could take inspiration and cues from the popular work by Lin-Manuel Miranda. I used the historical documents available to me at the time and leaned on expertise from Lyman-Mersereau. Chaplain Medeiros also provided me with additional insight via historian Peter Young.

The production began with meetings designed to ground the importance of the subject matter. After reading Lyman-Mersereau’s poetry, Chaplain Medeiros quickly envisioned how it might be turned into a piece of theatre that could take inspiration and cues from the popular work Hamilton by Lin-Manuel Miranda. If that could be done in three to four months, it would be a testament to our teamwork.

Punahou School was established by some of these missionaries and the approaching date of February 17th 2018 held great significance as it marked the 200th anniversary of ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s passing.

Retired Punahou faculty Marion Lyman-Mersereau authored a five-page poem encapsulating key moments in ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s life journey, and I was contracted to compose music, write a libretto, choreograph, and direct a show derived from that poem. Punahou drama faculty Heather Taylor served as Assistant Director and Costume Designer. The resulting production was titled A Hip Hop Retelling of the Life of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia.

I have experienced so many blessed moments along this journey with this amazing cast and with Assistant Director Heather Taylor. We have explored parallels and intersections of a life journey rooted in native culture, adversity, newfound faith, identity, and the significance of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia's genius. We hope the combination of elements borrowed from 'Oli (chant), Mele (melody), Rap, Spoken Word, and the polyrythms of Hula and Hip Hop Music help to reinforce the idea that our hero's story can be viewed as a personal mixing and remixing of experiences and ideas that ultimately led to the beautiful legacy we are celebrating today.

In the fall semester of 2017, Punahou School Chaplain Lauren Medeiros invited multidisciplinary artist Jonathan Clarke Sypert to join a collaborative team to create a Hamilton-inspired piece of musical theatre for middle school students grades six through eight, that would celebrate the life of a significant figure in Punahou’s origin story. Retired Punahou faculty Marion Lyman-Mersereau authored a five-page poem encapsulating key moments in ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s life journey, and Jonathan Clarke Sypert was contracted to compose music, write a libretto, choreograph, and direct a show derived from that poem. Punahou drama faculty, Heather Taylor served as co-director and costume designer.

The resulting production was titled A Hip Hop Retelling of the Life of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia. The epistemological journey to create this work included ethnography, theology, and dance offer theoretical paradigms to understand hip hop as a vehicle for knowledge transfer and the production of storytelling. Throughout the creative process, the cast of young artists and production crew were asked how personal experiences as lifelong learners may be effectively translated through live embodied performance. Grounded in vocal production and movement practice, the young artists also inquire how calling upon their ancestry and reflection on their personal place in their communities situates them as responsible artists in Hawaiʻi.

“NARRATOR GROUP 3

He stood up one day

on the steps at Yale

He was the boy who came with Thomas

Now he's un-furling his sail

'ŌPŪKAHA'IA

And I've

always longed to learn

something, anything new

Now I have the words to make a difference

Let me show what I can do”

Give Me Learning, Scene 7

The Creation Process

Upon first reading I immediately saw how Lyman-Mersereau’s poetry inspired Chaplain Medeiros to connect a potential staging of the content to the aesthetic vehicle Hamilton. The meter, rhyme, and imagery were a lovingly exquisite blending of educational resources and pride in heritage. At five pages long, this overview of the life of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia captured my attention and dedication to fulfill the project. Poem in hand I set about composing and writing a libreto.

One of the first things I did was to reference my previous works. One of my daily artistic expressions is music production via my digital audio workstation, FL Studio. I’ve produced hundreds of audio files that no one besides a select few has ever heard. I thought I might easily identify something from my vault that I could use. Recordings from my previous Hip-Hop musical, Comfortable Cages were my initial starting point since I had some cutting room floor material there. I decided on one track from that project. I looked into other folders labeled “untitled”, “various”, “please sort me”, and “stuff”. I found two more tracks that I thought captured the sound of adventure and hope. I located one more that had a voyaging theme and I began to feel hopeful. Then I found a nearly hour-long recording of me noodling on a piano and decided I would sample myself. After twenty minutes of chopping, rearranging, and adding bass and drums to this sample, I realized I had just made a crucial instrumental for the show. This piano recording was made in a classroom called Bishop 111, during a summer of teaching for the Clarence T.C. Ching PUEO Program at Punahou School. I felt like this was providence. After finalizing each of the tracks, writing lyrics and blocking, and creating choreography for nine pieces of music, I recorded myself performing each song and sent the cast a rehearsal track about twenty minutes long.

During the process there were some setbacks with school schedules, winter vacation, and a period when I fell ill, that exacerbated an already short timeline. It was during this time that I began to truly feel the weight of my initial delay in responding to Chaplain Medeiros’s invitation to take on the project, the balancing of my day job and gigs, and an overall reactionary execution of my duties versus the proactive approach I knew this project deserved. I also knew I couldn’t let this feeling of weight further impact the production, so I drank my lemon ginger tea, pulled up my bootstraps, and got back to work. There were kalaʻau to cut, sand, and stain.

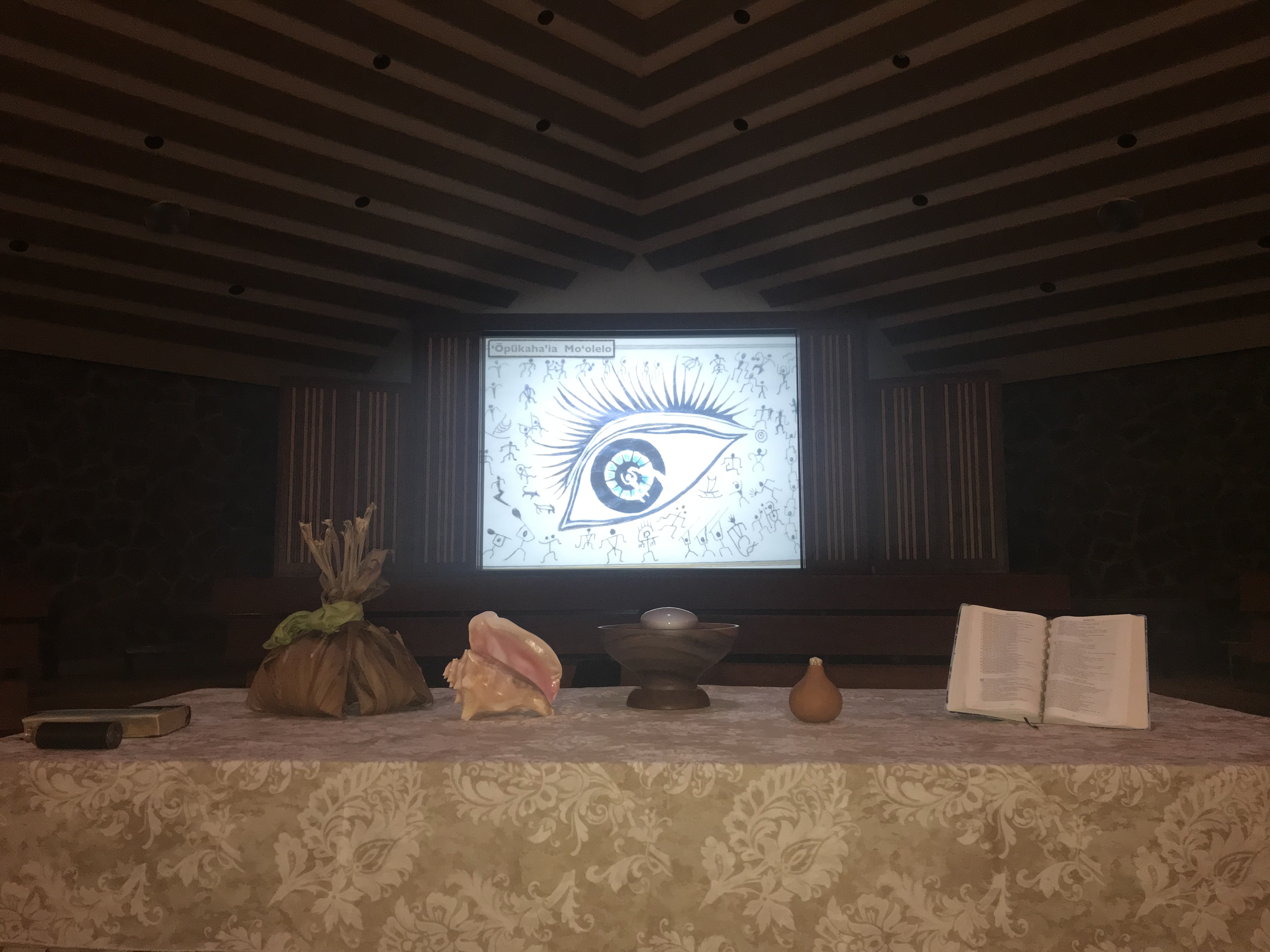

With the approaching debut of this production, we looked to our checklists to make sure we had completed all of the visual design elements. Thurston Memorial Chapel serves as the spiritual heart of Punahou. With 500 seats the chapel is most commonly used for Chapel Program services, school performances, and faculty and staff meetings. Early on it was decided that due to time constraints and the facilities available to us at Thurston Chapel, we would take a minimalist approach. Sean Alterado served as our audio-visual technician and used the chapel’s lighting presets, ran our audio from a computer, and I would supply images for projection.

I met Polynesian visual artist Glenn Freitas years ago when he gifted me a hand-crafted image of a He'e (Hawaiian Octopus). His images come to him in his dreams, and he wakes up every day with new inspired creations rooted in his connections to traditions, ancestors, and faith. The image of the "Eye with Petroglyphs" was one such work that I imagined held ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia at the center, navigating his awakened sense of purpose under the grace of God. Surrounding him in this blessed presence are the symbols of people and their stories. While these images may hold unique significance for each viewer, Glenn and I see all of our stories connected in a rotating tapestry of discovery with divine inspiration at the center.

On Wednesday, January 24th, it all came together for a performance in front of the cast’s middle school peers. On Friday, January 26th, they performed for a full house including their friends, family, and descendants of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia. The shows were a joy to behold, and the work felt worth every moment.

“ENSEMBLE

He was only

ten years old when our story unfolds/

our hero was in Ka’u on the Island of Hawai’i/

to unite the chain a war was being fought/

guns were acquired Guns were aimed and fired

men were being shot/

spears were thrown and caught but many hit their mark

as Kamehameha’s warriors made their way

and struggled through the dust and dark into the light of each

warring day

The boy saw his home destroyed”

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, Scene 1

Missed Opportunities to Apply Methodology

The production began with meetings designed to ground the importance of the subject matter. Our first in-person meeting was held at Thurston Memorial Chapel, located in the heart of Punahou School. The chapel area also includes a “roundhouse” classroom, an open courtyard, and chaplains’ offices. This location is full of rich history due to the spring kapunahou (“the new spring”) that bubbles there to form a pond that still exists today under and around the chapel. The grounds of Punahou school were initially lands given to Christian missionaries by King Kamehameha’s widow and Queen Regent Ka‘ahumanu, so that they would have a water-fed area to grow food and support their mission. These are the same missionaries who took an interest in Hawaiʻi because of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia. This land would later be chosen as the site of Punahou School. I realized how deep and rich the history and legacy of the man we were going to honor through our project.

Even still, any epistemological approach I took in the creation of this project came from intuition, referencing previous personal knowledge and works, or accepting what was quite literally handed to me and therefore lacked any intentional use of research methodology. Any and all methods I am about to mention here are retrospective labelings of my actions.

In my director's note I included, “It has been an honor for me to be a part of this rare creative opportunity. Production teams, singers, dancers, and actors anywhere, dream of having a part in developing an original show that is based on a story rooted in their own histories.” While these feelings are true, any future production would include dedicated time to investigate the histories of the cast members. In Urmimala Sarkar Munsi’s article “Practice-Informed Pedagogies of Cultural Unlearning” she writes, “In this balance between practical experiment and critical reflection it becomes important to allow a certain flexibility and freedom of choice to students to generate ideas for research projects related to the course. Such a peda- gogy approaches unlearning as a task of both teachers as well as students, seeking what action researcher Peter Reason has termed a ‘co-operative inquiry’”. If I were to remount this show we would have at least one workshop designed to inquire into the inherent epistemology of the cast and look for bridges between that body of knowledge and the content of the production.

Thomas F. DeFrantz’s chapter “HIP-HOP HABITUS v.2.0” in the book Black Performance Theory, provides a host of ideas for how our use of Hip-Hop in the show could have been more intentional beyond the aesthetic application inspired by Hamilton. Admittedly I was excited to use my skills and background as a multidisciplinary Hip-Hop artist, but I could have taken a neutral approach and practically asked myself, my collaborators, and especially my cast, “why Hip-Hop?” According to DeFrantz, “Hip-hop can be narrated as a return to the real in its aggressive rhythmicity, its lyri- cal directness, and its physical abundance of heavily accented movements. These performance qualities of hip-hop (echoed in graphic stylings of vi- sual arts associated with the genre) suggested a truthfulness of expressive gesture that predicted possibilities of communication across boundaries of race, class, and location if not gender, sexuality, or age group. For hip-hop’s first generation of scholars and journalists, hip-hop claimed expansive space as a necessary voice of expression for the disenfranchised; for its second-generation interpreters, it became a connectivity for youth across geography, practiced locally.” Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s story begins with disenfranchisement and through his determination and grit, and the assistance of key figures along the way, he becomes this figure of historical recognition. That is the archetype for many a Hip-Hop success story.

The production’s cast came to the project with varying degrees of knowledge and abilities, and I saw great examples of that during the auditions. When we began our rehearsal process I tasked myself with further education and training the cast in singing, dancing and acting, the three pillars of musical theatre. This was something that could, and should, have been delegated to more production partners. In “The Place of Artistic Research in Higher Education” Martin Blain and Helen Julia Minors write, “Partnerships fall within specific contexts: the institutional context, and the personal research context.” Whereas the institutional context described here refers to collaboration with HEI Higher Education Institutions, I am referring to the artistic and financial partnership I agreed to with Punahou School and my personal partnership with Chaplain Medeiros. Medeiros kept in constant contact with me and offered lists of potential collaborators and research resources. John Roberts, Alicia Scanlan, James Anshutz, and Mike Lippert are people who are fantastic resources in middle school musical theatre, choral education, and digital music creation that she suggested and that I neglected to engage, at an unknown loss to the project. Peter Young is an amazing historian who has written extensively about ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, with whom I also did not establish a connection. How much richer would the content of the production have been? Again, we do not know.

Thinking back to the time when we got deep into the thick of rehearsals, I now see an opportunity to engage with more spaces on the Punahou campus than our middle school classroom and Thurston Chapel. “Dancing Earth: Seeds Roots Plants and Foods, from Origi Nation to Re-Generation” by Rulan Tangen provides a beautiful example. “The rehearsal process begins where these gifts were given: outdoors, where for decades I have danced when I haven’t been able to access studio space, finding movement in collaboration with wind, rock, grass, on pavement where weeds sprout between cracks. Sometimes we are chased through parks by authorities demanding license to gather (yes, that still happens). All of this is our ‘land-dance’ practice.” A Hip Hop Retelling of the Life of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia deserved some time dedicated to exploring the grounds of Punahou School, and would have greatly benefited from the circular Indigenous Research Paradigm suggested by Shawn Wilson, because “what is more important and meaningful is fulfilling a role and obligations in the research relationship - that is, being accountable to your relations. The researcher is therefore a part of his or her research and inseparable from the subject of that research (J. Wilson, 2000). The knowledge that the researcher interprets must be respectful of and help to build the relationships that have been established through the process of finding out information. Furthermore, the Indigenous researcher has a vested interest in the integrity of the methodology (respectful) and the usefulness of the results if they are to be of any use in the Indigenous community (reciprocity).”

I also see how a dance dramaturg might have been an incredible boon to our endeavor. Upon reflecting on my choreography for the production, I see where I sacrificed clear and meaningful action for merely representational imagery and derivative movement that didn’t necessarily add to the messaging in songs or scenes. In “Cut the Sky: Traces of Experimentation in Dance and Dramaturgy in the Age of the Anthropocene,” Pigram and Swain write that “we wanted to give form to ways of knowing and doing and being that exists in Indigenous knowledge systems and approaches to “caring for country.” There are several deeper layers I could have explored through movement.

Blain and Minors have more manaʻo, “We have a professional (as well as moral) responsibility to work in an ethical manner…” and that “the responsibility extends to considering how one deals with sensitive material (which may relate to political, societal or soci-ety concerns). In addition, issues around copyright and censorship also are of concerns when developing collaborative work.” There was a moment, after the production, when I thought about the work I had done and inquired about rights to the creative product of the show. I imagine this to be at least a bit offensive, and although I chalk this up to inexperience I do feel it was a question that came across more self-serving than I intended. Going forward I understand that “...problems can become creative opportuni- ties, and with a shared strategy in place from the start of the project, potential ethical issues can be resolved as early and as quickly as possible; as such, we propose that ethical responsibility in a collaborative artistic research context should go beyond compliance.”

“NARRATOR GROUP 2

He moved from home to home

he worked summers for his keep

Poring over tomes

Improving on his speech

He was a good student

And he knew that he was meant

to be a scholar

He looked for knowledge not a dollar”

- Heartbeat, Scene 6

“'ŌPŪKAHA'IA

‘Above all things

make your peace with God

and make Christ

your friend.

Aloha ‘oe.

My love be with you.’”

Step Out On Faith, Scene 8

Conclusion: Thoughts for Future Productions

Many lessons were learned in this grand endeavor. I do believe more opportunities were available than I had taken notice of. Chaplain Medeiros extended herself and recommended many members of the Punahou faculty and alumni who would have been amazing resources at numerous stages in this production. I acknowledge this at the same time I accept that the work I contributed to my production team and the performances we pulled out of our cast is a testament to dedication, hard work, and luck favoring the prepared.

Should I have the opportunity to remount this production or be on the creative team for another concept that holds historical and cultural significance at its core, I will engage in more ethnographic research by reaching out to resource specialists in the form of cultural practitioners, historians, descendants of real-life characters, choreographers, composers, and musicians. I see how Hawaiian musical instruments could have been effectively used in the recorded score, especially when the pu is heard at the beginning of the overture. I realize how that might have signaled to listeners that Hawaiian music and sounds might be expected to reappear later in the score as recognizable samples or even as more overt referencing of traditional mele and oli. This is a project of its own that begs to be initiated.

My next steps are to share this document with the partners that made this production possible, and who have my everlasting gratitude. It my my hope they are reading this now, and if they are…that you know how much I appreciate you.

Mahalo nui loa.

Bibliography

Blain, Martin, and Helen Julia Minors. “The Place of Artistic Research in Higher Education.” In Artistic Research in

Performance through Collaboration, edited by Martin Blain and Helen Julia Minors, 11–36. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38599-6_2.

DeFrantz, Thomas F., Anita González, and D. Soyini Madison. Black Performance Theory. Durham, N.C: Duke

University Press, 2014.

Sarkar Munsi, Urmimala. “Practice-Informed Pedagogies of Cultural Unlearning.” In International Performance

Research Pedagogies, edited by Sruti Bala, Milija Gluhovic, Hanna Korsberg, and Kati Röttger, 139–49. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53943-0_10.

Tangen, Rulan. “Dancing Earth: Seeds Roots Plants and Foods, from Origi Nation to Re-Generation.” Dance

Research Journal 48, no. 1 (April 2016): 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S014976771600005X.

Wilson, Shawn. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Halifax Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing,

2008.